How Traders Make Money: Scrap Metal

In many ways, calculating a profitable scrap trade is not unlike calculating a profitable concentrates trade. The terminology is different but they operate in a similar fashion, albeit on much smaller tonnages per contract. Scrap metal, whether it’s copper, lead, zinc, etc. is sold on a discount to exchange prices. This could be on an outright number in USD/mt such as $300/mt discount to the LME price, or a discount in US cents per pound such as $0.40/lb discount to the CME price. Contracts using these formulas will use 100% of the LME price and then subtract the discount. This is important when it comes to the hedging as you will see shortly.

Discounts can also come in the form of percentages, such as buying scrap metal at 92% of the LME price. It is also not uncommon for traders to buy scrap at a fixed price, $2200/mt for example, however they will be making the calculation vs. the equivalent LME price at the time. In that example, if the LME is trading at $2400/mt, then essentially they are buying at a $200/mt discount to the LME. Contracts that use percentages of an exchange price to set a discount are handled differently from a hedging perspective.

There are far too many different types of scrap to list, and the discounts (either fixed amount or percentage) vary dramatically from metal to metal and product to product. But whatever product a trader is handling, their P&L is going to be calculated the same way. The products, geographical locations, discounts, and percentages payables I use in my examples may well be different from the actual market but the logic behind the calculations remains the same.

If a scrap trader hedges (which by now hopefully you agree they should!), their job is to buy metal at a larger discount than the discount they give when they sell the metal, taking into account all of their other costs involved in moving the product from supplier to consumer. If X = the purchase discount, Y = the sale discount, and Z = the trader’s additional costs, then if X - Z > Y then the trader will make a profit.

Let’s first look at a trade that uses a fixed discount to an exchange price. A 200mt scrap aluminum purchase bought at a $400/mt discount to the LME, FOB Baltimore. With additional costs to move the product to their sale basis CIF Rotterdam of $150/mt, this means that their breakeven sales discount would be $250/mt. If they have to offer a larger discount than $250 they will lose money, any discount less than $250 and they will make a profit.

Scrap Trading P&L Table

Here they have locked in a sale at a discount of $200 to the LME, and are therefore making a profit of $50/mt. Note that the hedgeable tonnage was 100% of the contracted tonnage as this was a fixed discount deal, not a percentage of the LME.

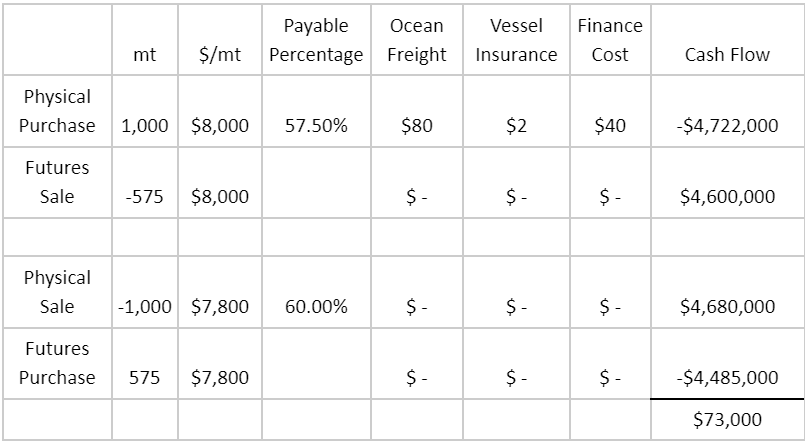

Looking at a percentage payable-based deal, take a trader buying 1000mt of brass copper at 57.5% of the LME, FOB Guayaquil, Ecuador, and they have a sale at 60% of the LME basis CIF Shanghai. They have additional costs (Ocean freight, vessel insurance, and finance costs) totaling $112/mt.

Percentage-based trade P&L Table

Buying at 57.5% of the LME copper price means they are receiving a discount of 42.5%. Selling at a payable of 60% of the LME copper price means they are only giving a 40% discount on the sale. This 2.5% margin, minus their additional costs, gives them a profit of $73/mt. Note that the hedgeable tonnage when using percentage payables reflects only the payable tonnage (exactly like a hedge for a concentrates trade). You are not paying for/cannot charge for 100% of the commodity, if you were to hedge 100% of the tonnage you would be creating a huge exposure to the exchange price, rather than negating it.

Discounts are typically a direct reflection of the supply/demand for each commodity and market - which can vary considerably between geographical regions. If discounts are high, this suggests that there is a lot of material around - sellers need to offer large discounts to buyers as buyers have a lot of sourcing options. If discounts are low, buyers have fewer sourcing options so are willing to pay more for the same product. Traders will often take a view on the market that discounts will change. If they think that the market will tighten they may choose to get long physical at today’s discount in the hope that when they sell the metal in the future the discount will have decreased and they will make a profit. Conversely, if they think the market will loosen they may choose to sell at today’s discount in the hope that by the time they cover the sale, discounts will have increased and they will make a profit.

Scrap trading and the related discounts are often a lot more volatile than refined premiums or concentrate TCs because scrap dealers are a lot more reactive to outright prices of commodities. Making sure you understand all of these concepts is vital to long-term success in the industry.