The Natural Hedge

Often when discussing hedging with companies they tell us that it’s not a high priority for them because they have a natural hedge. While on occasion this can be true, most of the time their understanding of a natural hedge is flawed and they are actually running large outright price exposures.

But what exactly is a natural hedge and why are so many companies misinformed about their risk? When we talk about hedging price risk, we are trying to negate the risk that if the price of a commodity moves up or down compared to a physical purchase or sale price, it can negatively impact our profits on that physical business. A natural hedge means that as part of our physical business operation, purchase and sale prices are being offset against each other, and therefore underlying price risk is not created.

There are some examples of this where it can work, and it can be a great way to reduce the strains of Initial and variation margin on commodity companies. However, it is extremely easy to get this strategy wrong and when this happens, instead of saving money it is very likely the company will in fact lose money.

For example, let’s say a refined zinc producer is buying 10,000 dry metric tons (dmt) of concentrate with 50% zinc contained and an 85% payable. This would give them an approximate 4,250mt of payable, hedgeable zinc. If they were buying this zinc concentrate over the LME average of December, their futures hedge would be to sell 4,250mt (or 170 lots) of zinc over that same time period. However, let’s say that they were also selling 4,250mt of refined zinc that they had previously produced over the same LME average of December. Instead of selling zinc futures for their concentrates purchase, and buying zinc futures to hedge their refined metal sale, their physical purchase and sale are perfectly offsetting their price risk. Their cash flows related to the price of the zinc in this example would look as below:

However, even in this most simple example, there are nuances that typically still require some hedging. Price risk is only 100% negated if the tonnages of the physical purchase and sale are exactly the same, and they are pricing over the exact same QP. If the concentrates purchase is pricing over the average but the refined sale is pricing on the Monday prior 3rd Wednesday cash settlement, they would not be offsetting each other.

Let's say that their refined metal sale QPs were split, with 50% being over the same December average as the concentrates purchase, but the other half of the sales being priced on the Monday prior to 3rd Wednesday on the LME. If the price on the Monday prior 3rd Wednesday was lower than the December average, this would cause a loss.

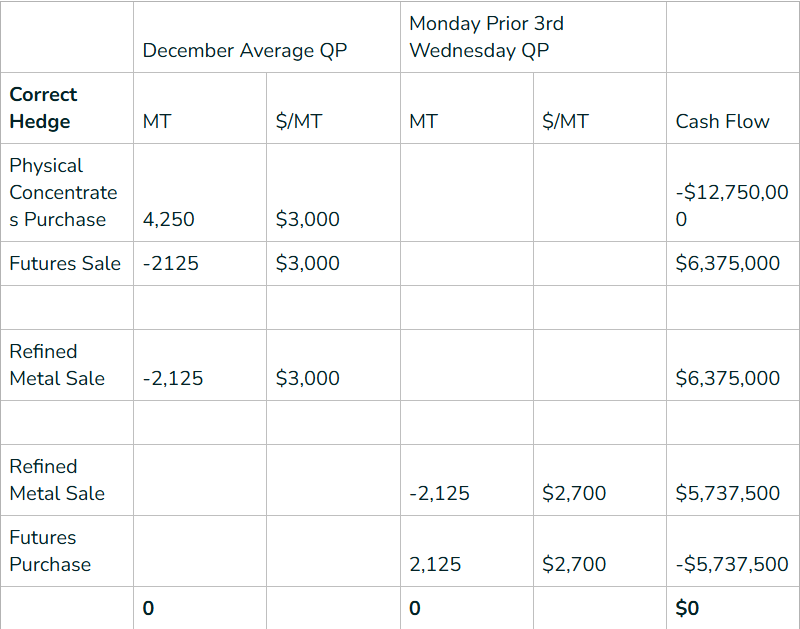

By not matching their QPs on their physical purchase and sales, the company is short 2,125MT at the Monday prior 3rd Wednesday price of $2,700/mt. This settles against the higher December average price of $3,000/mt and creates a loss of $637,500. They should have hedged 2,125MT of their concentrates purchase that didn't perfectly align with their sales QP by selling futures over the average of December, and used a prompt date of the 3rd Wednesday of December (a December on December average), and then bought back those futures when they hedged their physical sale, which would have looked as below:

For end consumers of metal, very rarely is it even as simple as the above example, and yet we often hear that consumers don’t hedge because they believe they have a natural hedge in place. Whether consumers are buying refined metal outright, recycling scrap metal, or procuring their refined metal through a tolling operation, they are still going to be paying for that metal based on a formula that is linked to an exchange price. If they neglect to hedge those purchases, no matter the means of obtaining the metal, they often create outright price exposure.

End consumer product prices are often set well in advance of being produced and companies cannot easily change final sale prices based on their actual cost of production. While this is possible over time (as we’ve all seen with recent inflation!), it is not a quick process and prices on the shelf react a lot slower than exchange prices do. Unless the final sale price of that product is moving up and down dollar for dollar with the purchase price of the metal, that company does not in fact have a natural hedge. A company that has a known breakeven on their cost of production that doesn’t hedge, is actually purely speculating on the price of that metal. They may not realize it but by not hedging they are gambling with the profits of the company.

You will often hear companies say “Things even out over the course of a year”, but pricing purchases or sales over an average, even over an entire year does not guarantee any hedge against those underlying prices. We are extremely fortunate in base metals that there are multiple highly liquid exchanges available where we can hedge our outright price risk. Not doing so, whether it is because of a misunderstanding of hedging or because they aren’t set up operationally to hedge, is an unnecessary risk.

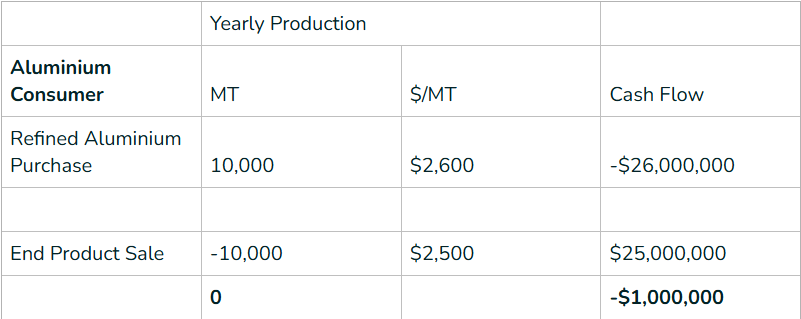

Take a consumer of refined aluminium that fixes the cost of their final product with a metal contained equivalent of $2,500. This means that if they end up paying more than $2,500/mt for their physical purchase of aluminium they will lose money on their end product sale. If they buy their physical aluminum at a price lower than $2,500 they will make a profit. Often these companies think that because they are buying and selling aluminium they are protected against the outright prices. However, let's say that the average price they end up paying for their aluminium over the course of the year is $2,600/mt. They would be making a loss of $100/mt on their product as per below:

However, if at the start of the year when the aluminium market was trading at $2,400/mt they had entered into forward futures purchases, they could have guaranteed a margin of $100/mt as per below:

Hedging can certainly add a level of complexity to reporting and accounting, but explaining how hedging works to an accountant or shareholder is a lot easier than explaining to that same person why the company profits are down 50% just because the price of metal increased or decreased unexpectedly. The flip side to hedging is of course that if prices move in your favor after you’ve hedged, prices decrease for a consumer of metal for example, then you won’t see any upside in profits. But given the volatility in prices and the access we have to metals exchanges, leaving profits up to chance is not wise, especially if your reason for not hedging is that you don’t fully understand how it works.